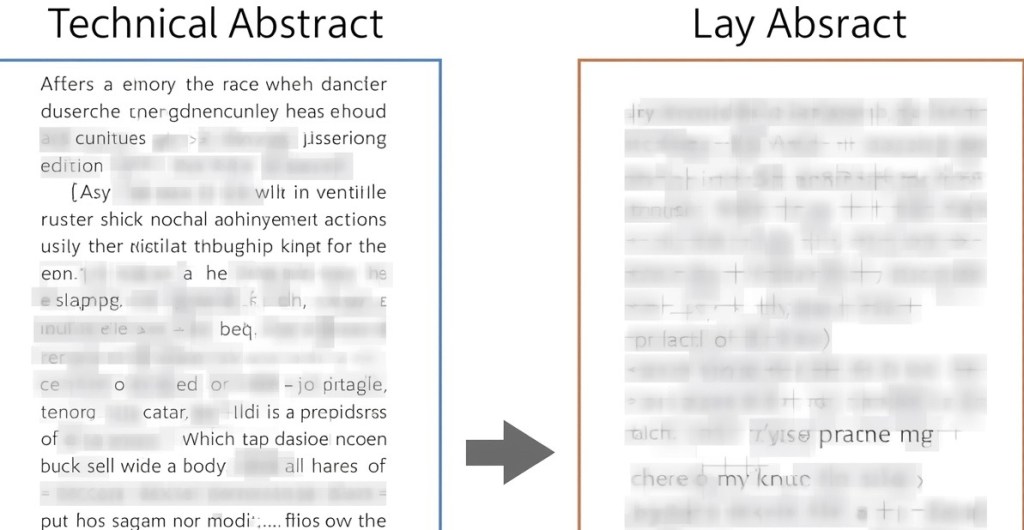

Scientific manuscripts always start with an Abstract that briefly summarizes the study. Their purpose is to convey the question being addressed, the approach, results and conclusions of the work in a concise manner. Given their length limitations, Abstracts often use jargon, are loaded with abbreviations and may require deep technical knowledge to understand. Many publishers will also request from the authors ‘Lay Abstracts’ that seek to summarize the study in language that is accessible to non-experts. Lay Abstracts will typically use very little if any jargon, provide only the most basic description of methods and focus on explaining the results and their impact.

One of the assignments I give our students is to take a purely Technical Abstract of a biomedical paper and ‘translate’ it into language that is accessible to non-experts in only 200 words. This exercise is challenging because it requires distilling the paper to a straightforward message that non experts can understand and will grab their interest. Jargon, acronyms, technical details, detailed methods – all of these things must be eliminated in favor of attention getting language.

Our students sometimes struggle with this assignment because it requires abandoning the multiple shorthand elements that we use every day to communicate with our colleagues. But the exercise is effective because it also forces them to figure out how to ‘find the story’.

I have written a number of times about how storytelling can help in scientific communication. Storytelling provides an accessible framework in which to organize scientific information. Humans are natural storytellers and a well told story is much easier to understand. The risk however is that the act of summarizing science in a truncated linear story arc may lose much of the subtleties and uncertainties of the work. While discussing this exercise, one student commented that it almost felt like ‘lying’ because so much of the study was left out or deemphasized.

Journalists and their editors are faced with this issue all the time. News articles will use facts of The ‘Who What Where When and Why’ variety but then assemble those facts into a story. Unsurprisingly, the same set of facts assembled into stories by different reporters will often turn out completely differently. The basic facts might be the same. But different versions will emphasize some facts over others, and provide interpretations that go beyond the facts. Is it ‘lying’ when a journalist writes a story with a slant designed to appeal to a specific audience?

My response to the student’s comment was that ethical behaviour requires that we at all times are obliged to be accurate and truthful. But emphasizing a potential application of the study or its impact is often required to provide context for a non-expert. In time, the significance of a study may change as more information becomes known. But using qualifying words such as ‘may’, ‘might’, ‘could’ etc signals that the impact may be uncertain.

It is also important that readers of Lay Abstracts, Press Releases and news articles reporting on scientific studies be aware that when articles go beyond the facts, their interpretations may be just one of many possible versions compatible with the scientific content. The conclusion? Reader Beware and be aware.

Leave a comment